Fragrances are made up of multiple facets, each supplying a different characteristic to the overall scent experience. While singular notes have their own smells individually; together, they form a scent composition, or what we’d call a fragrance or perfume.

For instance, in considering an iconic perfume like Chanel No.5, it might be useful to understand what some of the notes smell like on their own, like jasmine (a heady floral) and sandalwood (a sweet wood). Yet, a composition has its own unique style rather than just the sum of its parts. There’s a delicate dance of ingredients to find the right balance and achieve the desired intent, and the finished product has a life to it. There’s a movement to experiencing a scent. That is, we can smell different layers of a fragrance and witness how the notes change and move with our imagination and interpretation. If we can listen to our noses, they might just tell us what we’re smelling.

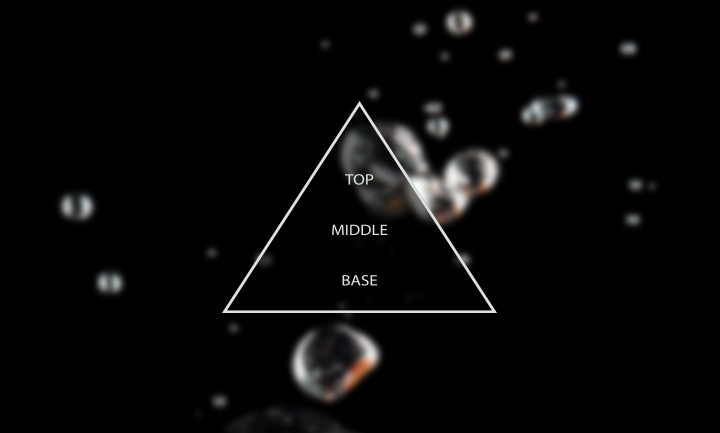

Learning to decipher and describe fragrances is a practice, and there are a few tools we can use to express our ideas about what we’re smelling. Fragrance compositions are often a blend of many fragrance notes. In describing fragrance, we can separate these notes into three distinct categories: top, middle, and base notes. Fragrances open with their top notes, mellow to their central middle tones, and finally give way to their anchoring base notes. This succession is a product of the notes’ longevity – or how fast the different ingredients evaporate. For example, the top notes of a scent composition have the lowest longevity, evaporating the quickest so that they hit your nose first. These notes draw the smeller in, acting as the head of the fragrance and lasting only about 15 minutes after application or diffusion and making up about 20% of the composition. Top notes are comprised of citrus and aromatic molecules, such as lemon, bergamot, lavender, and eucalyptus. Middle notes have a medium longevity, lasting about 30 minutes after the top notes evaporate. These middle notes are recognized as the heart of the fragrance, making up about 30% of its composition and providing the general theme of the composition. These thematic notes are generally pulled from floral, green, fruity, or spicy categories, such as the ingredients rose, grass, pear, cinnamon and jasmine. Lastly, the base notes are the highest longevity ingredients, meaning they last the longest, up to 24 hours, and provide the ‘aftertaste’ of a scent. These base notes are considered the foundation of the fragrance in which the scent is built up on, playing a supporting role to the more thematic and effervescent top and middle notes. For example, base notes are typically comprised of the likes of woody and balsamic tones, such as cedarwood, moss, vanilla, and Tonka bean.

The next time you have an opportunity to smell a fragrance, see if you can decipher between the top, middle, and base notes, and notice which impressions hit you first, and stay with you the longest. Classifying fragrances in this way allows us to build more of a language around scent and gain a more central understanding of what a composition smells like. Smell, experience, and interpret – follow the invitation of your nose.